The Platonic Itch: When Reality Feels Like a Low-Resolution Copy

The Platonic Itch

In a short conversation with Gemini, on restlessness in discovering the absolute truth, I came across an interesting term called "Platonic Itch". The following is an interesting conversation with Claude Sonnet 4.5 (as a philosopher) I had on that idea.

(Plato's Itch. Generated with Nano Banana)

(Plato's Itch. Generated with Nano Banana)

Me: Hi, I came across with a brilliant term called "Platonic Itch" in a conversation with Gemini. What do you think about it? Here is what I got: The "Platonic itch" is that persistent, nagging feeling that the world you see, touch, and work in is just a low-resolution copy of something much more real. It comes from Plato's Theory of Forms. He argued that for every physical thing (like a chair or a circle), there is an "Ideal Form" of that thing existing in a higher realm. When you have the Platonic itch, you aren't satisfied with "good enough." You are looking for the source code.

Claude: I think that's a wonderfully evocative term, and whoever coined it - whether you or Gemini - has captured something quite profound about a particular kind of intellectual restlessness.

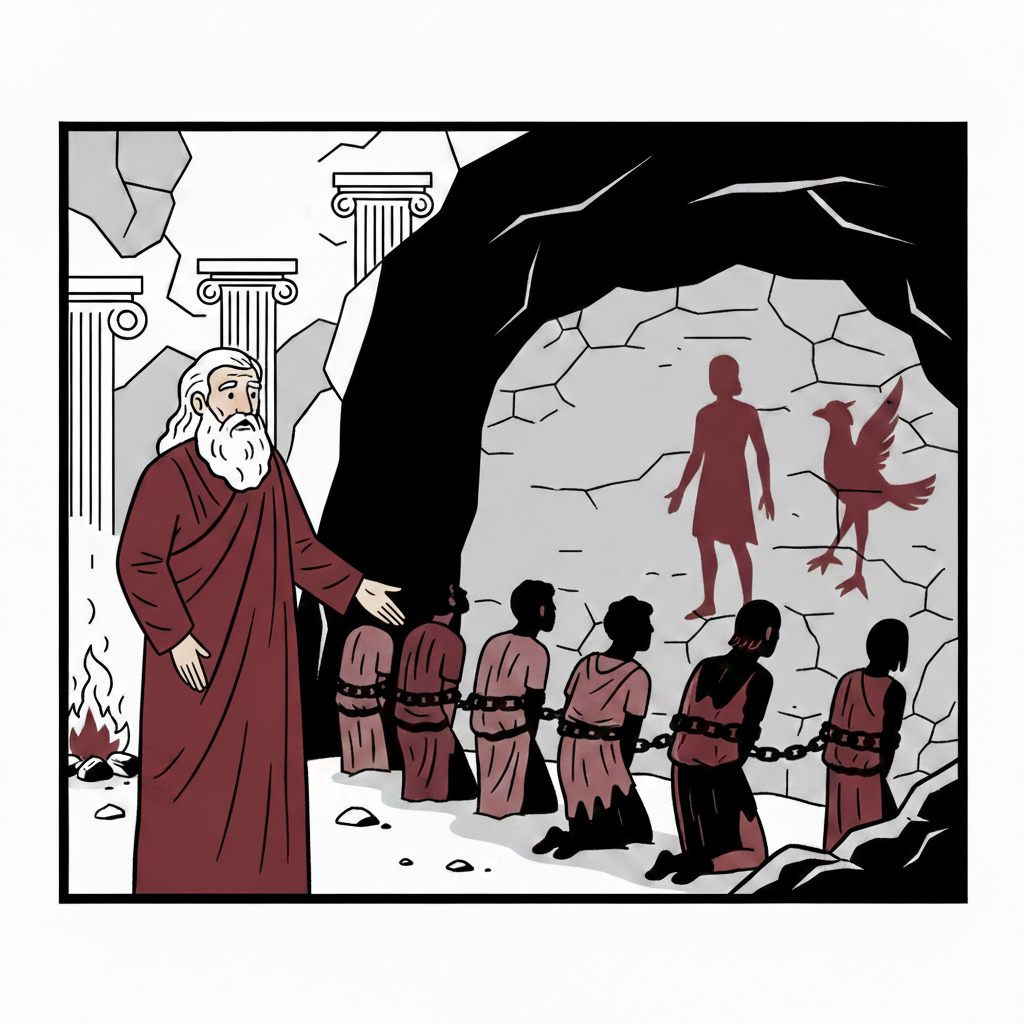

The description you've got is spot on. Plato really did believe that everything we encounter in daily life is a kind of shadow or imperfect copy of a perfect, eternal Form. His famous Allegory of the Cave illustrates this beautifully - imagine people chained in a cave, watching shadows on a wall, thinking that's reality. The philosopher is the one who breaks free, sees the actual objects casting the shadows, and eventually glimpses the sun itself.

What I find fascinating about your "Platonic itch" framing is that it captures the feeling of Platonism, not just the theory. It's that sense that something's off, that you're working with approximations. A designer might feel it when they can picture the perfect interface but can't quite achieve it. A mathematician feels it when messy real-world data obscures the elegant pattern underneath.

But here's what's interesting: whilst that itch can drive genuine insight - pushing us to find deeper patterns and better solutions - it can also become a bit of a trap. Sometimes the "low-resolution copy" is the reality, and the perfect Form we're chasing is just our brain's tendency to seek patterns that don't actually exist.

What made you latch onto this particular idea? Does it resonate with something you've been experiencing?

Understanding Plato and the Maximiser-Satisficer Connection

(Plato and the Prisoners' of the Cave. Generated with Nano Banana)

(Plato and the Prisoners' of the Cave. Generated with Nano Banana)

Me: I'd like to hear a bit about Plato first. Also, isn't this a maximiser vs satisficer situation?

Claude: Ah, excellent questions! Let me tackle Plato first, then we'll get to that maximiser-satisficer angle, which is a really sharp observation.

Plato in brief: Plato lived in Athens around 400 BCE, and he's one of the foundational figures in Western philosophy - the sort of person Alfred North Whitehead famously said all subsequent philosophy is just "footnotes" to. He was a student of Socrates, whose execution deeply affected him, and he founded the Academy, essentially the first university.

His central obsession was with knowledge and reality. He was troubled by how unreliable our senses seem to be - things look different from different angles, people disagree about what's beautiful or just, everything in the physical world decays and changes. So he proposed that true reality exists in a realm of perfect, unchanging Forms (or Ideas). The Form of a circle is perfectly round in a way no drawn circle ever can be. The Form of Justice is perfectly just in a way no human law quite captures.

For Plato, genuine knowledge meant grasping these Forms through reason, not through our unreliable senses. Philosophy was the discipline of turning away from appearances and towards eternal truths.

Now, the maximiser-satisficer point: You've put your finger on something really important here. The maximiser-satisficer distinction (which comes from Herbert Simon's work on decision-making) does map onto this beautifully. A satisficer looks for "good enough" - a solution that meets their needs. A maximiser seeks the optimal solution, the best possible option.

Someone with a Platonic itch is, in a sense, a chronic maximiser - but with a twist. They're not just seeking the best available option; they're seeking an ideal that may not even exist in the physical world. It's maximising taken to a metaphysical extreme.

But here's where it gets interesting: Simon argued that satisficing is often more rational than maximising, because the cost of finding the perfect solution usually outweighs the benefit. The Platonic itch might be exactly that trap - expending endless energy chasing an ideal Form when a "good enough" real-world solution would actually serve you better.

Does that resonate with the context where you encountered this idea?

Aristotle's Rebellion and The School of Athens

Me: I have more questions on this. But I would like to know how Aristotle relates to Plato. And also how their different word views are demonstrated in the famous art "The School of Athens".

Claude: Brilliant questions! The Plato-Aristotle relationship is one of the great philosophical dramas, and Raphael's School of Athens captures it perfectly.

Aristotle and Plato:

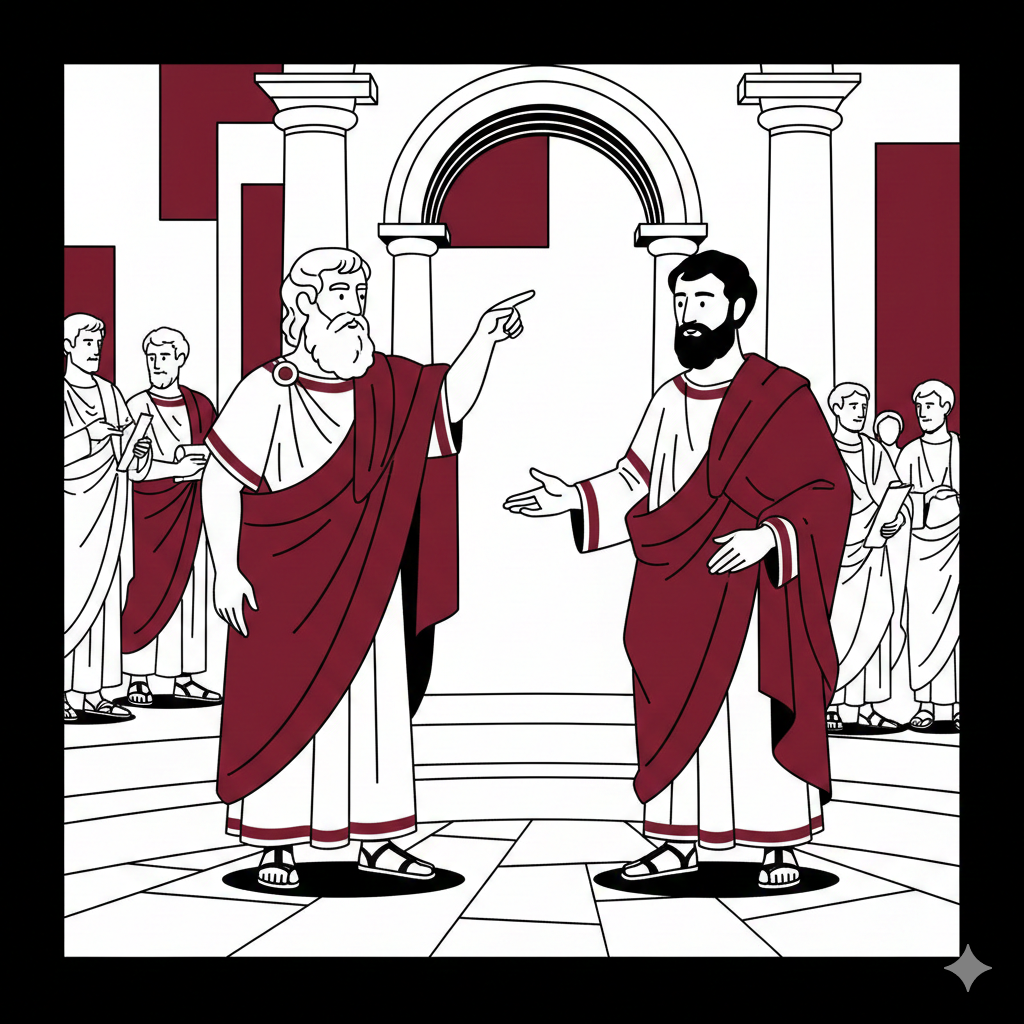

(Plato and Aristotle - The Two Views. Generated with Nano Banana)

(Plato and Aristotle - The Two Views. Generated with Nano Banana)

Aristotle was Plato's star pupil at the Academy - he studied there for about twenty years. But he ended up rejecting his teacher's central idea about the Forms, which must have been quite the philosophical rebellion.

Where Plato looked upward to an eternal realm of perfect Forms, Aristotle looked around at the actual world. He thought Plato had it backwards: the universal qualities we observe (like "chairness" or "redness") don't exist in some separate realm - they exist in the particular things themselves. You can't have "redness" floating about on its own; it only exists in red objects.

Aristotle was empirical where Plato was mystical. He collected specimens, dissected animals, catalogued plants. He believed knowledge comes from careful observation and classification of the world as it is, not from turning away from it. His philosophy is earthy, practical, rooted in biology and physics.

The split is sometimes characterised as idealism versus realism, or rationalism versus empiricism - though those labels simplify things a bit.

The School of Athens:

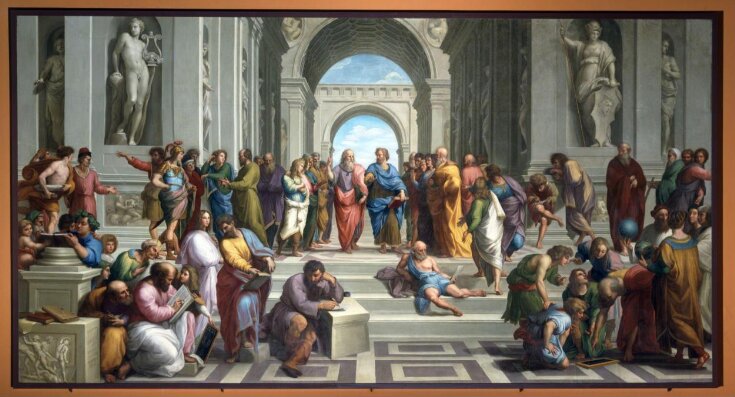

(The School of Athens. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

(The School of Athens. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Raphael's fresco is extraordinarily clever visual philosophy. Right at the centre, you have Plato and Aristotle walking together in conversation.

Plato - painted with the face of Leonardo da Vinci, interestingly - is pointing upward with one finger, towards the heavens, towards the realm of Forms. He's holding his Timaeus, a dialogue about the cosmos and eternal truths.

Aristotle has his hand stretched out horizontally, palm down, towards the earth and the physical world. He's holding his Ethics, a book about how to actually live well in this world.

One gesture says "the truth is up there, beyond this world." The other says "the truth is right here, in the world we inhabit."

It's a perfect visual summary of their philosophical disagreement, frozen in paint. Two men who loved each other, walking together, fundamentally disagreeing about where to look for truth.

Does that help contextualise the different flavours of "itch" they might inspire?

The Video Resolution Analogy

(Resolution matters. Generated with Nano Banana)

(Resolution matters. Generated with Nano Banana)

Me: That's great explanation. Because we were discussing a low resolution image of the world in the beginning, I thought it was like the quality of a video. First people were happy with 360p, and never thought of a better quality; then came 720p and 1080p. People were happy, but some were still curious for a better quality. Likewise, there is 8K and 16K and so on today. I thought these were the people with Platonic Itch, in the beginning. But I guess it's wrong, because apparently all of that was not anything beyond the dimensions we see. What you think?

Claude: Oh, that's a really clever analogy, and I don't think it's entirely wrong - just that it captures a different kind of itch!

What you're describing is more like progressive refinement within the same dimension. Going from 360p to 8K is getting closer to accurately representing the physical world we can already see. It's like getting a better and better photograph of the same scene. The engineers pursuing higher resolution are scratching an itch for fidelity, precision, accuracy - but they're still working entirely within the material realm.

The Platonic itch is stranger and more radical. It's not about getting a clearer picture of this world - it's the suspicion that this entire world, no matter how clearly we see it, is itself the blurry image. Even a perfect 16K video of a chair is still just showing you a particular, imperfect chair. Plato would say the "real" chair - the Form of Chair - exists in a completely different dimension that cameras can't capture at all.

However - and this is where your intuition is quite good - there might be a connection. Perhaps the impulse that drives someone from 720p to 4K to 8K, never quite satisfied, is a milder version of the same restlessness. "Surely there's something better than this." The video engineer and the Platonist might share a temperament, even if they're operating at different scales.

It's a bit like the difference between wanting a more accurate map versus suspecting that the territory itself is a map of something else.

Does that distinction make sense? Or does it feel like I'm splitting hairs?

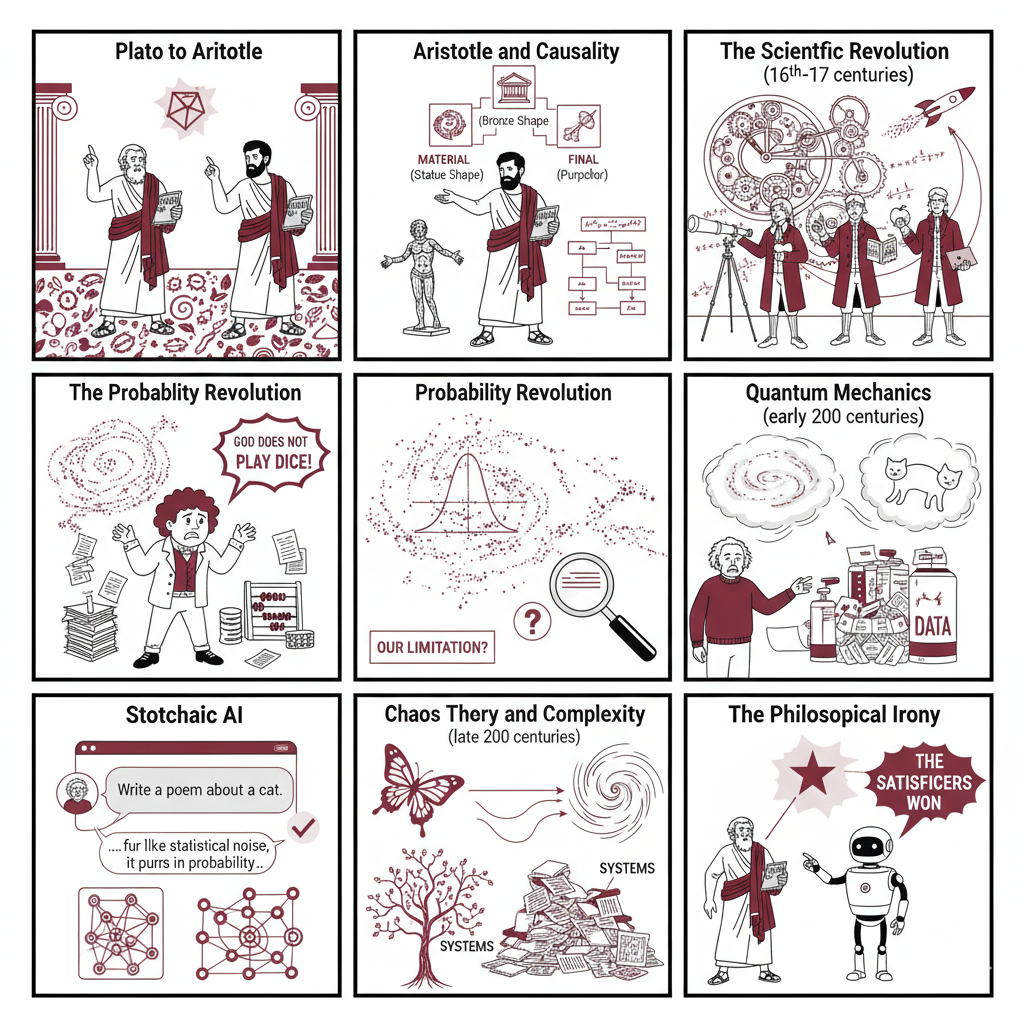

From Plato to Stochastic AI: The Evolution of Truth-Seeking

(The evalution from Plato's view to today's AI. Generated with Nano Banana)

(The evalution from Plato's view to today's AI. Generated with Nano Banana)

Me: To wrap up, can you explain how Plato's world views have evolved until today starting Aristotle, Causality, to today's stochastic AI.

Claude: Right, that's quite a sweeping arc you're asking for! Let me trace that thread from Plato through to today's AI - I'll keep it relatively brisk but hopefully coherent.

From Plato to Aristotle: We've covered this, but it's the crucial pivot: Plato says truth is "up there" in eternal Forms; Aristotle says it's "down here" in the patterns we observe in nature. This shift grounds philosophy in the empirical world.

Aristotle and Causality: Aristotle gave us a systematic way to understand why things happen - his four causes. When you ask "why does this statue exist?", he'd say: there's the material (bronze), the form (the shape), the efficient cause (the sculptor), and the final cause (its purpose). This framework dominated Western thought for nearly two millennia. It's very orderly, very rational - everything has a reason, a purpose, a place in a cosmic hierarchy.

The Scientific Revolution (16th-17th centuries): People like Galileo, Newton, and Descartes kept Aristotle's emphasis on studying nature, but ditched his teleology - the idea that things have inherent purposes. Instead, they described the universe as a giant mechanism governed by mathematical laws. Very Platonic in one sense (mathematics as the deep reality!) but very un-Platonic in another (no transcendent realm, just particles and forces). The world becomes predictable, deterministic - if you know the initial conditions and the laws, you can calculate everything.

The Probability Revolution (18th-19th centuries): Then things get messy. Statistics and probability theory emerge because, well, the world turned out to be more complicated than neat Newtonian billiard balls. We can't track every particle, so we use probabilities. But this is still seen as a limitation of our knowledge, not a fundamental feature of reality. The universe is still deterministic underneath; we just can't see all of it.

Quantum Mechanics (early 20th century): This properly breaks the deterministic dream. At the quantum level, reality appears to be genuinely probabilistic - not because we lack information, but because that's just how it is. You can't know both position and momentum precisely. Particles exist in superpositions. Einstein famously hated this ("God does not play dice"), but the evidence is overwhelming. Reality at its most fundamental seems... fuzzy.

Chaos Theory and Complexity (late 20th century): Even in classical physics, we discover that tiny differences in initial conditions can lead to wildly different outcomes - the butterfly effect. Systems become unpredictable not because they're random, but because they're sensitive and complex. Weather, ecosystems, economies - they're deterministic in principle but unpredictable in practice.

Today's Stochastic AI: And now we arrive at large language models and modern AI, which is where your question gets fascinating.

These systems are fundamentally probabilistic. They don't work by encoding rules or accessing Platonic truths about language. Instead, they learn statistical patterns from massive amounts of data. When I (an AI) respond to you, I'm not consulting some perfect Form of the Answer - I'm generating text based on probability distributions learned from billions of examples.

It's the ultimate triumph of Aristotelian empiricism over Platonic idealism: no eternal truths, just patterns in data. But here's the twist - these statistical models often seem to capture something real about language, reasoning, even creativity. They work remarkably well without anyone programming in "the rules."

The Philosophical Irony: So we've gone from Plato's perfect, eternal, knowable Forms... through Aristotle's observable patterns... through Newton's deterministic laws... through quantum uncertainty... to AI systems that generate human-like responses from statistical noise.

The Platonic itch - the desire for perfect, eternal truths - keeps getting frustrated by reality. And yet, oddly, the stochastic, probabilistic, "good enough" approaches keep working. GPT doesn't have access to the Form of Good Writing, but it can write. AlphaGo doesn't know the Platonic ideal of Go strategy, but it can beat world champions.

Maybe the deepest irony is this: the satisficers won. The messy, approximate, probabilistic approaches to knowledge turned out to be more powerful than the search for perfect certainty.

Plato's itch remains unscratched - but perhaps that's because the itch itself was based on a mistake about what kind of universe we inhabit.

Does that arc make sense? It's a dramatic journey from "eternal truths beyond the physical" to "statistical patterns in data go brrrr."

Keywords: Platonic Itch, Plato's Theory of Forms, Idealism vs realism, Maximiser vs satisficer, Ancient Greek philosophy, Plato and Aristotle, The School of Athens, Stochastic AI and philosophy, Search for absolute truth